Amos Harel (Haaretz)

In the first hours following the huge explosion at the Beirut Port, the Israeli defense establishment worked hard to try and piece together a preliminary intelligence assessment of what happened. The incident that shook Lebanon caught its neighbor to the south by complete surprise. Despite the evil victory tweets by irresponsible politicians and questionable journalists, the Israeli intelligence services had nothing to do with the explosion. It seems that its impact, though, will affect not only the balance of forces in Lebanon but the tensions between Israel and Hezbollah as well.

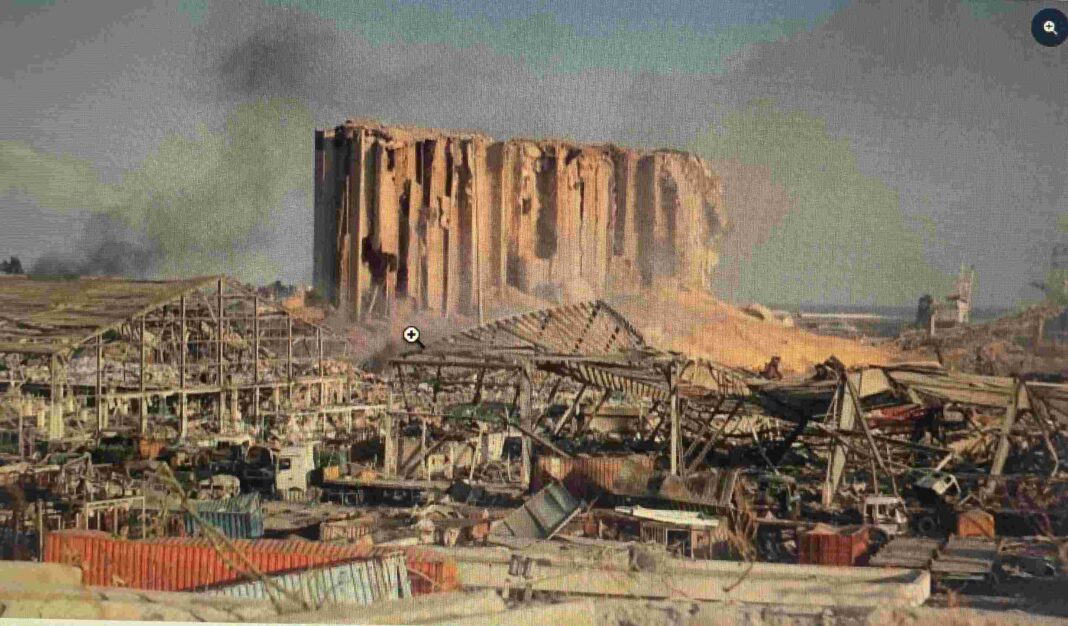

The initial reports from Lebanon said the tragedy was due to an explosion of a fireworks deport. During the night and morning, a more credible version emerged: A huge depot of ammonium nitrate, a dangerous substance used by industry and for the production of agricultural fertilizer, exploded. There have also been instances in which the substance was used to prepare explosives. It is still unclear exactly who was responsible for these materials, whether it was being stored legally and who was responsible for monitoring it.

Lebanon has been described for decades as a corrupt country that is falling apart one that has trouble imposing law and order at the most basic level. Currently there are complaints about the state having ignored the security dangers at the Beirut Port and there are demands for the cabinet to resign over the disaster. Then there’s the elephant in the living room – Hezbollah. State authorities do not dare confront the largest armed force in Lebanon, a trend that has only worsened since the establishment of the latest government, one that is controlled to a great extent by Hezbollah behind the scenes.

This point is also relevant due to the site of Tuesday’s disaster – Hezbollah is always active at Lebanon’s entry points – and also due to the type of materials that led to the blast, which also have secondary military uses. All of Hezbollah’s military infrastructure is deployed in population centers throughout Lebanon – in Beirut, the Beqaa region near the border with Syria, and in the south of the country.

In recent years Israel has conducted an international campaign about this issue, with the aim of achieving two goals: to force Hezbollah to empty the military installations that surround it, and which it uses as a human defensive shield; and to prepare world public opinion for the possibility that many Lebanese citizens may be hurt, unintentionally, if and when a third Lebanon war were to erupt.

About two years ago, in his annual address at the UN General Assembly, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu presented maps and aerial photographs of sites where he said the Shi’ite organization had hidden weapons depots and sites where it improves the accuracy of its rockets. One of these sites was spotted beneath the soccer stadium in Beirut. A few days afterwards the Lebanese government invited diplomats and foreign press to visit these sites with the aim of disproving the Israeli claim. Between the speech and the tour, the telling material had apparently been swiftly evacuated from the sites. Participants in that tour told Haaretz they had easily spotted signs of fresh paint.

What will Hezbollah do now? The urgent question that worries Israel has to do with an unsettled score between the two sides. On July 21 a Hezbollah man who had been lent to the Iranian Revolutionary Guards was killed in an aerial attack, which was attributed to Israel, at the airport in Damascus. Since that time, sources in the organization have threatened a revenge attack. Last week, on July 27, an attempted response by the organization was thwarted when IDF forces, using deterrent fire, repelled a group of Hezbollah men who had crossed the border and infiltrated Israeli-held territory in the Har Dov area. Even after the incident, intelligence services assessed that Hezbollah would initiate another attempt, since the score had not been settled.

But the desire to do so takes on new proportions after Lebanon sustains more than 100 fatalities in the explosion in Beirut, and perhaps dozens if not hundreds of missing people buried beneath the rubble. Under these circumstances, it is hard to believe that Hezbollah would take the risk of another attempt against Israel.

The organization’s general secretary, Hassan Nasrallah, certainly knows he would have trouble justifying any deterioration of the situation to avenge the death of a single (borrowed) activist while his country faces the consequences of its most damaging incident in decades. Even the IDF understands this. If in the coming days we hear about a gradual thinning out of forces at the northern border, that will be the reason.

In the longer term, it seems Hezbollah faces an ever-worsening situation. Lebanon is deep in the throes of a huge economic crisis, which has worsened due to international economic sanctions over Hezbollah’s links to the government and to Syria and Iran. The extent of public anger could be seen at the beginning of the year during the many large protests against the economic situation, which also overlapped with the start of the coronavirus pandemic.

The previous balance of forces was very convenient for Hezbollah. The organization controlled what went on to a great extent but most complaints were aimed against the Lebanese government, and in recent years there were no real attempts to force the organization to disarm. In the long run, perhaps the Lebanese people – and citizens from all ethnic groups participated in the previous round of demonstrations – will force Hezbollah out of its comfort zone.

From Israel’s standpoint, a possible warning light has been lit. The last war with Hezbollah came in 2006 during a period when Nasrallah was under great internal pressure. The kidnapping of the two reservist soldiers on the border was perpetrated in an attempt to divert the flames of domestic discontent from Hezbollah. The effort went amazingly awry and embroiled Lebanon in an unnecessary war with Israel.

In the meantime

In the summer of 2010 Lord Michael Williams, the UN envoy to Lebanon made a brief working visit to Israel. In a conversation in Jerusalem, the British diplomat (who died three years ago) sounded very worried. Lebanon, the way he saw it, was at that time on the brink of a civil war. In the background, there were pressures on Hezbollah from the international tribunal investigating the organization’s involvement in the assassination of Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri five and a half years beforehand.

The dark forecast of Williams, a skilled and experienced observer of the Middle East, didn’t pan out. When a few months later the Arab world shake-up began, it did great damage to Lebanon’s neighbour but came close to passing over Lebanon entirely. Syria almost completely broke apart, but in Lebanon, perhaps because of the lasting trauma of the civil war of the 1970s, rival camps did not take up arms. The country survived and was even forced to absorb more than a million refugees fleeing the battles in Syria.

On Tuesday Lebanon experienced a terrible tragedy. It befell the country during a period of rising unemployment, millions of citizens living in poverty and a beleaguered power system supplying electricity to homes for only a few hours a day. Yet it’s too soon to bury it. Matters in Lebanon move at their own pace. (This week the verdict of the international court on the Hariri case is finally due to be published). One can cautiously assess that at some point the Lebanese will overcome the tremendous destruction left by Tuesday’s blast at the Beirut Port.