By Tatalo Alamu

There is something like grief-fatigue. When so many good and great people have passed and you no longer know how to mourn the dead. Death and dying have become so cheapened that life itself begins to resemble a grisly posthumous joke. Often, you recall that it has been quite a while that you last saw somebody only to be rudely reminded that you will never see them again. Welcome to the year of the mass-obituary and overcrowded departure halls.

The news came out of the blues like a thunderbolt. You were in the ancient town to pay your last respects to an illustrious son of the soil who was the latest to succumb to the grim reaper. Everything appeared dead: no light, no glow-worms, no properly working phones, no internet connection, no functioning Wi-Fi. With so many fallen slabs and decaying obelisks, even the old cemetery at the edge of the town appeared to be dying.

And yet you remembered that fifty years earlier, the same town was so brightly lit. At that period, the prospects of approaching Christmas festivity warmed the spirit and made the heart to glow. Hope and optimism lit the fuse of human yearning. The air then was stuffed with the aromatic smell of Harmattan-chilled palm wine which trumps even the most vintage of champagne brand.

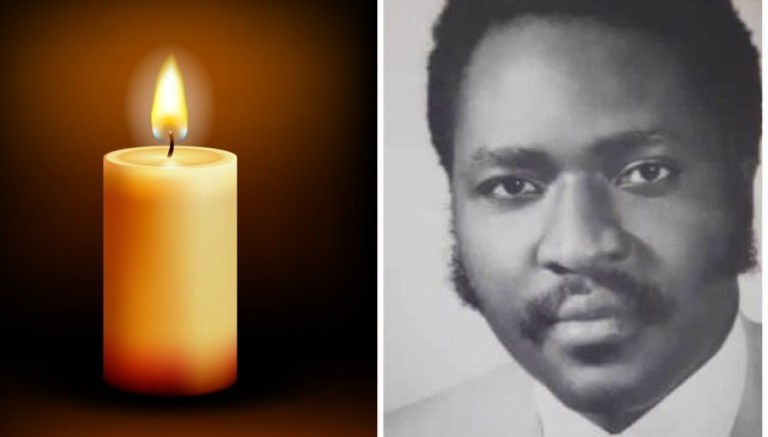

But this morning in the ancient junction town, there was funereal gloom everywhere. The nation is regressing to the Stone Age of human existence. As you fumbled your way towards the sitting room, the dead telephone screen suddenly glowered and a rogue solitary message appeared on the screen. It was from High Chief Niyi Alonge, and it was terse and to the point: Gbolabo Ogunsanwo died this morning.

For the next ten minutes, one drifted aimlessly around the sitting room in lonely agony trying to soak in the magnitude of what had happened. The mind wandered to the fact that Gbolabo Ogunsanwo had once graced the same sitting room with his august and lordly presence.

Together with Ayo Opadokun, the veteran human rights campaigner and NADECO chieftain, they had journeyed all the way from Lagos in affecting solidarity to grace the funeral ceremony of one’s older sister, the late Iyalode of the town. Years earlier, the duo had also been in attendance at a private family gathering to celebrate one’s diamond jubilee.

Anyone who had known the two gentlemen would know that these were hard men grilled in the no-hostage, “up and at em” Action Group school of agitprop politics. But they also had the milk of kindness and generosity of spirit flowing through them. They both took their friendship very seriously.

Gbolabo Ogunsanwo had an intimidating aura about him and a magnificent presence. Tall, swarthy and broad-shouldered, immensely self-confident and robustly good looking, there was a hint of elitist snobbery somewhere. He walked and carried himself forward with the swagger and self-assurance of the old Ijebu segment of the Yoruba aristocracy.

There was something about his imperial and imperious carriage which could rub lesser mortals the wrong way. He was one of those men whose effortless air of natural superiority could be quite daunting to many. But he also had an infectious sense of humour and his crackling laugh could be heard for miles when he was truly in his elements.

But despite his charisma and undeniable star quality, it was his pen that brought him to national attention. He was a master of the written word. He wrote with a peculiar feel and flair for the English language which would have made the owners wince in envy. His column was strewn with literary allusions which spoke to a literary imagination. This ought not to have been a big surprise. He read English at the university and was the best graduating student in his final year.

Known to his many admirers as the Elvis Presley of journalism, he wrote with guts and gusto and was the past master of the abrasive put-down and devastating turn of phrase. Yours sincerely remember him dismissing a serving British minister of the early seventies, Sir Reginald Maulding, as given to Mauldin sentiments. A less fortunate former colleague was bluntly advised not to mistake “a ministerial toga for an opportunity for mandibular walkabout”.

It was elegant and combative journalism at its very best, delivered in joyous, surging prose. He was not given to lofty abstractions, concept-chopping or dense dialectical disquisitions. His forte was not the analytical rigour of the political scientist or the argumentative prowess of the philosopher of the human condition. If this made the writing very accessible and immensely popular, it also strikes at the core of journalism as a perishable commodity best suited for instant consumption.

With Gbolabo Ogunsanwo, Nigeria has lost one of its finest writers and most gifted children. His death throws up the awkward and troubling question of the problematic relationship among various segments of the Yoruba postcolonial elite. Whereas the feudal culture of the north allows it to identify its gifted and most promising scions right from youth and nurture them to political stardom, the reverse appears to be the case with a Yoruba world in turbulent and traumatic transition.

In this ethnic coliseum, the intellectual elite dislike and disdain the political elite while the political elite fear and disapprove of the intellectual elite except those they can bend to their will. The economic elite are scornful and contemptuous of the political elite while the military elite hold all of them in violent contempt and fearful derision. The result is often political chaos and a war of all against all in which everything available is weaponized.

Gbolabo Ogunsanwo himself often regaled friends and associates with his bitter experience in Yoruba politics. His talents and gifts naturally attracted the keen attention of Chief Obafemi Awolowo who brought him in to his innermost political circle. There was nothing the Ikenne titan loved better than quality argument and Ogunsanwo could be quite uproariously argumentative.

But one day after a particularly testy exchange with one of Awolowo’s famous political associates, Ogunsanwo began visiting the toilet with increasing urgency and a burning urge to urinate. After the eighth visit, it was a sweltering and groggy Gbolabo that managed to drag himself back to his seat whereupon Chief Awolowo called out his associate by his first name. “Tu omokunrin yen sile”, Awolowo ordered his associate in Yoruba. ( Release the young man).

A ritual of obeisance and submission was performed on a prostrate former editor whereupon Ogunsanwo suddenly regained his health and vivacity. Surely if the young man knows how to argue with elders and political superiors, he ought to have fortified himself with necessary metaphysical accoutrements. A Yoruba proverb put things with ominous clarity. “Enu agba o ko’le, enu omode o ko ilepa”. A youth who insists on flooring an elder must be ready to kiss his grave first.

Later in life, Ogunsanwo complained that the strategy moved from metaphysical impairment to fiscal disempowerment with Chief Awolowo’s political associates who had found their way to power making sure that they denied him the financial wherewithal to pursue an independent line of action.

The famed columnist fingered a former UPN governor who had denied him a certificate of occupancy over a parcel of land whose ownership he thought he had perfected as his chief tormentor in this regard. In the brutal world of politics, elementary political survival dictates that nobody furnishes a potential terminator with the weapon of choice.

As it is in politics so also it is in journalism. You must watch your back until your back begins to ache and your vision begins to blur. There is no paddy for jungle as they say in Nigeria and just because you are paranoid doesn’t mean they are not going to get you. There was a touching naivety and shortage of fundamental political nous about the departed great journalist.

By the end of 1974, Gbolabo Ogunsanwo bestrode the world of Nigerian journalism like a colossus. His personality was as captivating as his column was enthralling. The Sunday Times he edited with aplomb and brilliance reached a magical benchmark of over five hundred copies a week in February 1976, a stupendous feat by any global standard of the time.

At that point in time, there was nothing stopping Ogunsanwo from reaching the very summit of the organization. The entire nation was his oyster. The normal succession route was for the editor of the Sunday paper to accede to the editorship of the daily at the appointed hour. Having acquitted himself so well, everybody thought it was a question of time for Ogunsanwo.

By a quirk of fate and fortune, the unforeseen intervened. The military sacked their boss, General Yakubu Gowon, in a palace coup in August, 1975 while he was attending an OAU conference in Kampala. At the appointed hour, the two great intellectuals who edited both The Daily Times and The Sunday Times were nowhere to be found or seen. Instead, it was the master reporter and relentless newshound that carried the day.

Tipped off by a late Ogori general, Segun Osoba, a man of urban ubiquity, tireless social networking and reportorial sleuthing, worked his phone and contacts all night to get the details of the coup. Not only that, he braved the odds to get to the office after midnight to make sure the headline reflected the new reality. It was a major scoop.

So impressed was Alhaji Babatunde Jose by this feat of journalistic excellence that he promptly promoted Osoba, at that point the Deputy Editor, to the editorship of The Daily Times kicking Areoye Oyebola upstairs while leaving Ogunsanwo undisturbed at the Sunday Times.

Even though he was the one that pioneered the visionary Graduate Employment Scheme of the Times Group, Jose had himself risen through the ranks and was very fond of underdogs who excelled and surpassed themselves. He was himself a master social networker with impeccable connections. Although there was a hint of self-reversal about it all, Jose had made the point that the great newsroom is not a coven of supine and retreating intellectuals .

It was at this point that the falcon could no longer hearken to the falconer. A great gale of resentment and rebellion swept through the organization. Gbolabo Ogunsanwo teamed up with Areoye Oyebola and others to write a petition against their boss for his dictatorial and autocratic handling of affairs in the Times group. In the ensuing furore, Jose had to relinquish his chairmanship at only the age of fifty. His lifelong labour had been essentially completed.

But this was not the end of the story. According to his memoirs, Walking A tightrope, Jose noted that as he was about to conclude the formalities of handling over to the new chairman, Alhaji Aliko Mohammed, the austere gentlemen took him aside and told him that he was not going to allow his rebellious tormentors have the last laugh. Thereafter, a gale of retirements reverberated through the organization, sweeping off Ogunsanwo and the others.

A colourful and flamboyant journalistic career has ended in political mishap. Now in retrospect Ogunsawo at thirty two or thereabouts had also concluded his essential life labour. The rest, including half-hearted forays into business, a stint at publishing, a near derisory presidential run and a fiasco at the now rested Compass was as anticlimactic as it was nearly tragic.

There is one last anecdote that is quite revealing of the late journalist in his essential humanity and the awkward enclosures and encumbrances of his later years during which he became an ordained pastor of the Redeemed Church. Shortly after this column signed on, yours sincerely got an early morning call from an agitated and disturbed Ogunsanwo. “ Some el Qaeda suicide squad journalists have invaded the nation. Have you been reading one Tatalo Alamu in The Nation?” he hollered in his grand baritone.

When yours sincerely answered in the affirmative and feigned ignorance about the identity of the writer, Gbolabo ordered immediate investigation, asking one to report back to him post haste. A few days later, yours sincerely called him up to say that all investigations pointed in his direction and that many were already whispering his name as the pseudonymous writer.

“Ah won ti fe pami niyen!!!,” the great journalist screamed into the phone and the line went dead. (Now, they have decided to kill me!!) When the true identity of the person became known, he let out his prolonged crackling laugh wondering aloud how the tell-tale clues could have eluded him.

n sharp departure and for the sole purpose of elucidation, shortly after the column debuted, Aremo Olusegun Osoba, ever the master newshound, simply collared snooper at a public function and bluntly informed that it didn’t take him three weeks to find out the identity of the writer.

Despite all the triumphs and tribulations, it is Gbolabo Ogunsanwo’s crackling laugh and his essential humanity that remain with this writer. Not even death can take that away. May the great soul of this master journalist rest in peace.

The Nation

Do you have a story for Fedredsnews?

Email us at info@fedreds.com or send a WhatsApp message to 08083064630

Twitter: @FedredsNews